Sir Aurel Stein, a prominent explorer and archaeologist, left an enduring mark on the world of historical exploration and preservation. His expeditions to Dunhuang, a remote and historically rich region located in modern day China, stand as a testament to his unwavering dedication to uncovering ancient treasures and ensuring their protection for future generations. Here we delve into the remarkable journey of Sir Aurel Stein as he embarked on a quest to Dunhuang, detailing the challenges he faced, the meticulous methods he employed, and the lasting legacy he created in the realm of archaeology and historic preservation. Stein’s story is a testament to the power of systematic exploration and the impact it can have on our understanding of the past.

Early Expeditions and Challenges

Stein’s desire to visit Dunhuang in 1902 was driven by a series of challenges he faced in his early expeditions. At the time, his applications to explore other regions, such as Afghanistan and Tibet, were consistently met with refusals. These setbacks heightened the urgency to secure permission and funding for his proposed Second Expedition, which was already in the works while he was still documenting his First Expedition in 1901.

Moreover, Stein’s decision to become a naturalised British citizen in 1904 had a significant impact on his ability to navigate the bureaucratic hurdles that often accompanied such exploratory ventures. This shift in citizenship made his position considerably easier and facilitated his pursuit of the Dunhuang expedition. Thus, Stein’s early expeditions and the challenges he encountered played a pivotal role in shaping his determination to explore Dunhuang, an endeavour that would eventually become one of his most renowned achievements.

Second Dunhuang Expedition and Preparation

As Sir Aurel Stein continued his work on “Ancient Khotan,” he simultaneously sought permission and funding for his Second Expedition, primarily aimed at exploring the historically rich Dunhuang region, located in China’s north-western Gansu Province, west of the Gobi Desert. The endeavour to secure these essentials was a persistent and intricate process, as he navigated the bureaucracy and financial constraints of the time.

Despite facing multiple obstacles, including financial constraints and the need for official authorization, Stein’s dedication and passion for his work led to a breakthrough. In 1905, he received the long-awaited permission to embark on his Second Expedition, and his efforts were bolstered by funding contributions from the British Museum and the British Government of India. This significant development marked a pivotal moment in Stein’s career, as it opened the door to the treasures of Dunhuang and set the stage for his enduring legacy.

Stein’s meticulous planning for this expedition, including securing the necessary equipment and supplies, ensured that he was well-prepared for the challenges that awaited him in the remote and arduous terrain of Dunhuang. His eight months of preparation were marked by a relentless commitment to detail, from packing essential items like notebooks, ink, and photographic materials to coordinating with his network of friends in Britain for the delivery of necessary equipment. These preparations were a testament to Stein’s methodical approach and unwavering determination to make the most of his forthcoming journey.

Methodical Approach and Travel Conditions

Stein’s methodical approach to exploration was a hallmark of his success during the Second Expedition. He maintained a strict and disciplined travel regimen, which set him apart from many of his contemporaries. Central to his methodology was the conscious decision to travel with a minimal crew, consisting mainly of his Indian and Central Asian assistants, while excluding any European companions. This approach gave him unparalleled control over the expedition and allowed for swift decision-making in the field.

Stein’s reliance on his local assistants was a defining characteristic of his method. His loyal assistant, Turdi, displayed remarkable dedication and resourcefulness throughout the expedition. Turdi’s ability to locate Stein in the most remote desert locations, even delivering bags of correspondence containing as many as 150 items, showcased the depth of their working relationship. On one memorable occasion, Turdi covered a staggering 1,300 miles in just 39 days, enduring harsh icy conditions and a lack of provisions to ensure he followed Stein’s tracks into the Lop desert. This kind of devotion and resourcefulness among his assistants was invaluable to Stein’s overall success.

Stein was diligent about keeping meticulous records during his travels, maintaining regular correspondence, and taking comprehensive notes. Even as he encountered potentially significant discoveries, he delayed investigating them in favour of keeping his notes up to date. This dedication to documentation showcased his deep understanding of the importance of preserving a detailed record of his expeditions for future analysis.

Discoveries at Dunhuang

The culmination of Sir Aurel Stein’s meticulous planning and methodical approach was the journey to Dunhuang, which commenced in April 1906 and reached its destination in March 1907. During this extended expedition, Stein continued his extensive correspondence and took meticulous notes, all while uncovering some of the most significant treasures of the region.

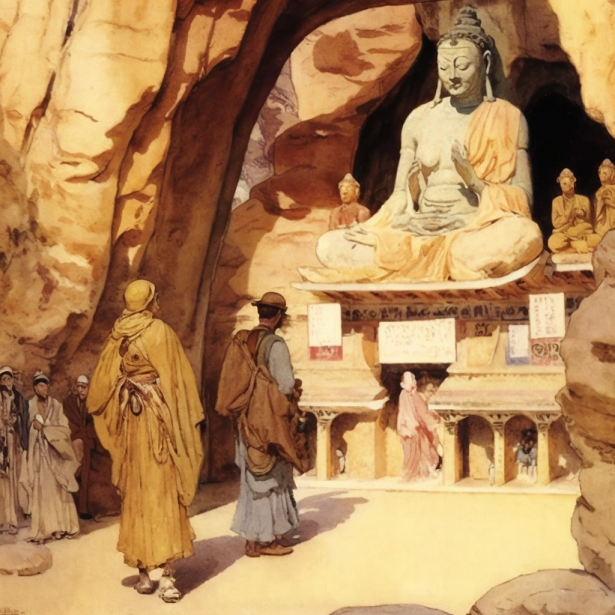

Upon reaching Dunhuang, Stein’s tireless efforts were met with rich rewards. He was the first Westerner to arrive in Dunhuang following the discovery of a cache of manuscripts and paintings at the ‘Caves of the Thousand Buddhas‘ at Ch’ien-fo-tung near Tun-huang. These findings, walled up and preserved for nearly nine centuries, were a remarkable discovery and would shape Stein’s legacy.

The importance of Stein’s work in Dunhuang is indisputable. It was not only a personal triumph but also a significant contribution to Western understanding of the region’s history and culture. The ‘enormous cache’ of documents, temple banners, and paintings was preserved and later distributed, with a substantial portion finding its way to institutions like the British Museum, the British Library, and the National Museum of India in New Delhi.

Stein’s remarkable achievements during the Second Expedition were officially recognized in 1912 when he was offered a knighthood. This recognition was a testament to the invaluable contributions he made to the field of archaeology and the preservation of historical treasures.

Post-Expedition Collaborations

Following the Second Expedition to Dunhuang, Sir Aurel Stein’s commitment to his findings did not wane. He recognized the significance of his discoveries and the responsibility to document and share them with the world. Stein’s work was characterised by a methodical and systematic approach, and this continued to be evident in his post-expedition activities.

One of the immediate outcomes of the expedition was the submission of an official report detailing his findings, and numerous “thank you” letters to various individuals and institutions who had supported his work. While these activities were essential, some aspects of his work were kept confidential.Among the details divulged in some of these correspondences, Stein emphasised the pristine condition of the discovered materials due to the dryness of the cave and the exclusion of atmospheric influences over many centuries.

He stressed the importance of protecting this sacred property, which included an enormous cache of documents, temple banners, and paintings, some dating back to the 9th-10th centuries AD. Stein requested that this part of the report be treated as confidential, reflecting his commitment to safeguarding these historical treasures.

As a methodical scholar, Stein always set aside time for detailed notes, which could be transformed into publications soon after his return. His ability to balance exploration with documentation was a testament to his dedication. His publications, including “Ruins of Desert Cathay” and “Serindia,” provided a comprehensive account of his expeditions and findings.

Additionally, Stein was mindful of his correspondents and contacts, even during the disruptions of World War I when communication between Hungarian and British subjects was forbidden. His relationship with Hungarian geologist Lajos Lóczy, which had initially prompted his journey to Dunhuang, continued to be a source of guidance and mutual respect.

Legacy and Ongoing Relevance

The legacy of Sir Aurel Stein’s systematic and meticulous approach to exploration and preservation endures to this day. His work in Dunhuang and beyond has left a permanent effect on the field of archaeology and the understanding of history and culture in Central Asia and China.

Stein’s extensive collections, which include manuscripts, paintings, artefacts, and photographs, are invaluable sources for the study of mediaeval China and Central Asia. These collections continue to be a cornerstone of research, with scholars and institutions actively working to catalogue, digitise, and study the wealth of materials he acquired.

In a contemporary context, the Mellon Foundation’s support for the digitization of Stein’s collections and other Dunhuang-related materials has opened up new avenues for researchers. High-quality digital images and virtual tours of the caves at Dunhuang are providing unprecedented access to these historical treasures. Stein’s legacy is evolving with the digital age, allowing for international collaboration and scholarly exchange on a global scale.

Additionally, the British Library’s International Dunhuang Project has made over 30,000 manuscripts available for online viewing, further expanding the reach of this valuable resource.

Sir Aurel Stein’s methodical and organised approach to exploration and preservation has left an enduring legacy that continues to shape our understanding of history and culture. His commitment to documenting and protecting historical treasures has paved the way for contemporary scholars to build upon his work, ensuring that the legacy of Stein’s expeditions lives on. His remarkable journey to Dunhuang and beyond exemplifies the power of a systematic and dedicated approach to unravelling the mysteries of the past for the benefit of future generations.