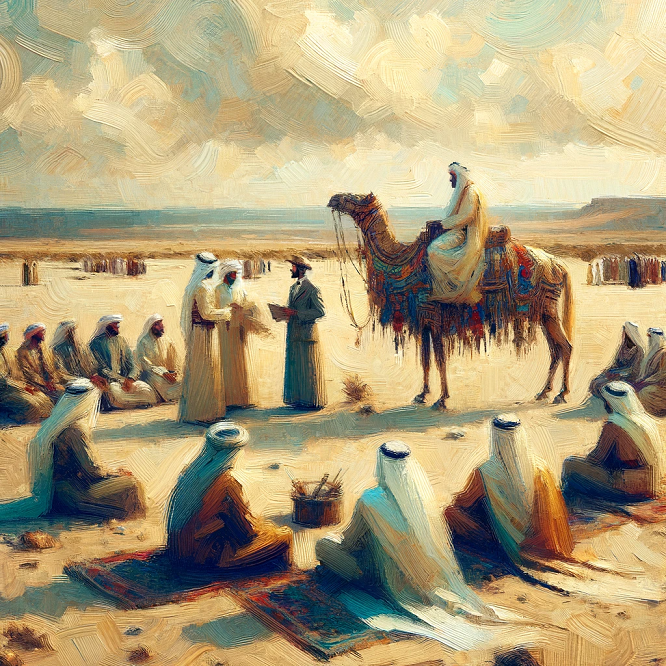

Lady Anne Blunt’s “Pilgrimage to Nejd” takes readers on a captivating journey through the Arabian desert, offering a unique glimpse into the geographical, political, and cultural landscape of the region. Blunt’s insightful observations and encounters during her travels shed light on the complexities of the Arabian Peninsula, making her books essential reading for those interested in exploring the history and traditions of the Middle East.

Departure From Jawf

Upon the 12th of January, Lady Anne Blunt’s party bid farewell to Turki and Areybi at Ibn Ariks’ farm. The departure was witnessed under a shroud of thick fog that blanketed the environment, adding an ethereal quality to the moment. Notably, their host, Nassr, expecting traditional parting gifts, felt a twinge of disappointment.

With the farewell formalities done, the party set its course in a southerly direction. The terrain they traversed was marked by mounds of sand hills, invoking images of the vast dunes of the Sahara or Sinai. Indeed, the journey was taking them deep into the heart of Central Arabia.

On route, Lady Blunt observed local people going about their daily tasks. Shepherds tending to their flocks and women gathering firewood became the scenes of their journey. Among these everyday observations, there was a significant encounter. Mohammed, one of their traveling companions, had an exchange with the woodland gatherers. The conversation was casual, revolving around life, expectations, love, and Mohammed’s bride-to-be. It was such encounters that helped the party to broaden their understanding of the local customs and people of the region.

We met several shepherds with their flocks, sent here to graze from the town, and parties of women gathering firewood. Mohammed amused us very much all the morning,talking with these wood gatherers. He had managed to get a glimpse of his bride elect and her sister before starting, and fancies himself desperately in love, though he cannot make up his mind which of the two he prefers. Sometimes it is Muttra, as it ought to be, and sometimes the other, for no better reason, as far as we can learn, than that she is taller and older, for he did not see their faces.

Pilgrimage To Nejd: Lady Anne Blunt

Encounter with Villagers in Kara

Eight miles into their journey from the farm of Ibn Ariks, Lady Anne Blunt and her party reached the village of Kara. The village offered a striking break from the uniformity of sandy terrain with its rocky mound, which emerged prominently amid the vast desert, and a grove of palm trees providing a picture of life amidst the arid landscape.

Upon their arrival in Kara, the travellers were greeted by a wave of shared community news from the villagers. The information pointed out that going forward, their journey would be within the territories governed by Ibn Rashid, assuring them a degree of safety common to these parts. Ibn Rashid, known for his fair and stringent rules, did not tolerate any form of highway robbery under his jurisdiction. This affirmation meant that the party could now relax from the constant worry of encountering bandits or raiders along their route.

Formerly Kara, like Jof and Meskakeh, was a fief of the Ibn Shaalans, and they still pay a small tribute to Sotamm, but in return they make the Bedouins pay for the water they use. There is no danger of being attacked by the Roala or anyone else, for we are in Ibn Rashid’s country now, where highway robbery is not allowed.

Pilgrimage To Nejd: Lady Anne Blunt

The encounter with the villagers provided a crucial understanding of the socio-political climate during this era. Lady Blunt’s journey, being within the safety of Ibn Rashid’s territory, also emphasizes not only the geographical demarcations of the region but the influence of tribal and regional governance during the period.

Traversing Through Nefud and Meeting the Howeysin Tribe

On January 13, Lady Anne Blunt and her party proceed through Nefud, a secluded and incredibly vast region that, contrary to its deserted appearance, boasts an array of vegetation. Nefud, often considered an epitome of stark desert landscapes, surprised the travelers with its unexpected sprouts of greenery, subtly flaunting the inherent resilience and adaptability of life within the harsh terrains.

In the midst of traversing this imposing landscape, Lady Blunt notes an intriguing phenomenon specific to desert geography – the presence of ‘horse-hoof hollows’ or ‘fuljes.’ These formations, depressions shaped strikingly similar to horse hooves, managed to pique the interest of the party due to their uniqueness and apparent abundance on the desert floor.

It is during this time in Nefud that they come in contact with the members of the Howeysin tribe. At first misjudged as the Roala, through active conversation, the visitors quickly learn about the distinguishing traits separating the two tribes. This interaction further enunciates the immense diversity existing within the nomadic tribal communities of the region.

I asked Mohammed … how it was that in the desert each tribe seemed so readily recognized by their fellows, and he told me that each has certain peculiarities of dress or features well known to all. Thus the Shammar are in general tall, and the Sebaa very short but with long spears. The Roala spears are shorter, and their horses smaller. The Shammar of Nejd wear brown abbas, the Harb are black in face, almost like slaves, and Mohammed told me many more details as to other tribes which I do not remember. He said that Radi had recognised these people as Howeysin directly, by their wretched tent.

Pilgrimage To Nejd: Lady Anne Blunt

The journey through Nefud and the meeting with the Howeysin tribe serve several purposes within Lady Blunt’s narrative. These encounters offer both, an interactive lesson in unique geographical features typical of such desert landscapes and an opportunity to delve deeper into understanding the intricate tribal patterns and identities prevalent in Arabia during Lady Anne Blunt’s journey.

Arrival and Encounter in Shakik

Continuing her chronicles, Lady Anne Blunt and her companions find themselves in the valley of Shaqiq on January 14. The existence of the valley is punctuated by the legendary wells, said to have been there since the dawn of time. Often surrounded by a shroud of historical reverence, the total of four wells in Shaqiq were far from ordinary. Reaching depths of a staggering 225 feet, these reservoirs are treasured boroughs from the past, testimonies to ancient innovation and engineering in the harsh desert environment.

Observing local life in Shaqiq, they encounter members from the Ibn Shaalan tribe, evident from their distinct tribal adornments and customs, who were occupied with drawing water from the deep wells. A sense of familiarity descends over the group when Lady Blunt recognizes an old acquaintance among the tribal members, a man named Rashid. Given the immense landscape of the Arabian desert and the nomadic nature of its residents, such an encounter seems to amplify the interconnectedness within the region, while underlining its small world phenomenon.

There was a dead camel near the well, on which a pair of vultures and a dog were at work, but nothing else living. While we were looking over our ropes, and wondering whether we could make up enough, with all the odds and ends tied together, to reach to the water, a troop of camels came flourishing clown upon us, cantering with their heads out, and their heels in the air, and followed by some men on deluls. These proved to be Ibn Shaalan’s people, and, to our great surprise and delight, one of them, a man named Rashid, recognized us as old acquaint- ances. We had met him the year before at the Roala camp at Saikal far away north.

Pilgrimage To Nejd: Lady Anne Blunt

The arrival at Shaqiq, the ancient wells and the chance meeting with Rashid, provide another stratum of understanding about the complex geographical, socio-cultural and historical tapestry of Arabia during Lady Blunt’s journey. The discovery of the wells illuminates another achievement of ancient civilizations, a survival technique perfected over generations. Additionally, the encounter with Rashid serves as an element of human connection, illustrating that while their journey was often marked by barren lands and vast deserts, the thread of human contact and relationships remained ever-present.

Rashid’s Hospitality and its Impact

Meeting Rashid was more than a chance encounter for Lady Anne Blunt and her companions; it was an unplanned yet welcome respite in their journey. Rashid, noted as a friend from past days, not only recognized them, but immediately extended an offer of hospitality that resonated with the traditional codes of Arabian ethics, in which generosity to visitors and travellers is highly valued.

Integral to this spontaneous display of fellowship was the provision of water, a priceless commodity in the harsh desert climate. Rashid, aware of the immense challenges that the desert journey presents, arranged for the travellers access to the water from Shaqiq’s fabled wells. This gesture not only literal aid but also symbolic relief. As they quenched their thirst and replenished their water skins, their spirits buoyed. This act of generosity embodied the spirit of Bedouin hospitality- one that cherishes communal solidarity and support, even in the face of harsh desert realities.

The impact of Rashid’s hospitality was palpable on the travellers. Water, often taken for granted in more fertile lands, carried an unparalleled significance in their desert journey, becoming a sustenance of life. Thus, Rashid’s act of generosity was more than a favour; rather it was a life enabling act that triumphed over the environmental harshness of the region. For Lady Anne Blunt, this was not only a restorative encounter with regard to their physical strength but also a heartening instance that seems to have rejuvenated their spirits. Rashid’s hospitality, therefore, served as a poignant reminder of the human bonds and personal relationships that pervade these seemingly desolate terrains.

Rashid at once offered to draw us all the water we wanted, for he had a long rope with him, and coffee was drunk and dates were eaten by all the party.

Pilgrimage To Nejd: Lady Anne Blunt

In sum, this encounter with Rashid underscored the value of hospitality and the role it plays in mitigating the challenges of survival in the arid Arabian landscape. For Lady Blunt and her companions, the encounter with Rashid encapsulated the essence of Arabian generosity and resilience, and indeed cast a warm, human light on their “Pilgrimage to Nejd.”

Conclusion

Lady Anne Blunt’s “Pilgrimage to Nejd” paints a vivid portrait of the Arabian desert, offering readers a profound insight into the geographical, political, and cultural landscape of the region during her travels. Through her detailed observations and engaging encounters, Blunt’s journey unfolds as a tapestry of both personal exploration and scholarly documentation.

By weaving together these experiences, Lady Anne Blunt’s narrative not only serves as a travelogue but also as a valuable historical account that enriches our understanding of the Arabian Peninsula during the period. The significance of her encounters, interactions, and observations underscores the intricate tapestry of the desert landscape, characterized by vibrant cultures, ancient traditions, and enduring human connections.