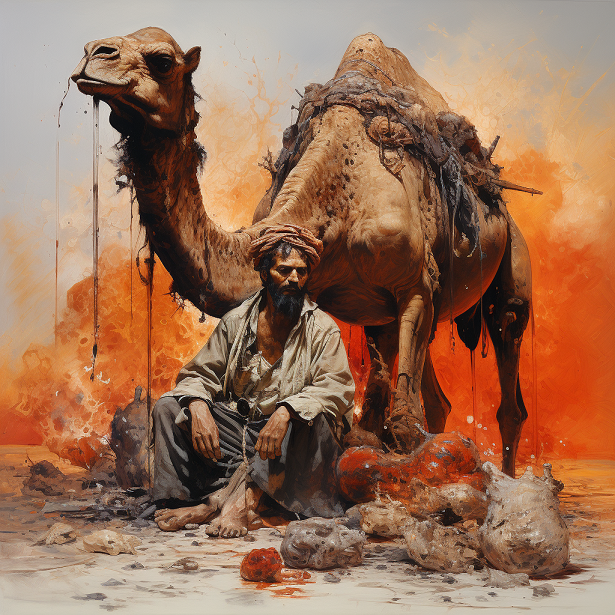

In the vast and challenging landscape of the Arabian desert, John Keane finding himself weary and worn, on a journey from Mecca to Madinah as part of a vast pilgrim caravan in the mid 19th century. The pilgrims, deceived by mirages, eagerly anticipate the sight of Rabigh, a major stopping point approximately halfway between Mecca and Madinah. Two hours before noon, a Bedouin guide points out a grove of date-palms that seemingly emerged from the plain, a couple of miles ahead. Despite its apparent proximity, the caravan takes two hours to reach Rabigh, a Turkish fort located a mile inland from the nearest sea port. The fort overlooks the sea, where a handful of small dhows bob at anchor.

Rabigh Ottoman Fort

The allure of Rabigh extends beyond its fortifications. A broad stream of the sweetest water encountered in the Hejaz region runs close by, enticing the weary travellers. The journey to the camping ground involves crossing this stream, triggering a spirited stampede as both humans and camels eagerly quench their thirst. The campsite, a grassy open space beneath the towering walls of the Turkish fort, provides respite and a chance to recover from the arduous trek.

Keane paints a vivid picture of Rabigh’s Turkish fort, a square structure with battlemented walls rising thirty feet high, devoid of ditches or additional defences. Each corner is flanked by a tower, home to rusted and ageing ship’s cannon. Despite their useless state, these cannons contribute to the fort’s imposing facade. The fort’s gateway faces the sea, and nearby, the Bedouin town of about two hundred huts offers provisions such as fresh fish, mutton, and vegetables.

The narrative unveils the communal dynamics of the caravan, with tents pitched and supplies brought in for a hot and satisfying supper. The culinary offerings are a welcome departure from the monotonous diet of cold boiled rice, stale chupatties, and dry dates endured in the preceding days. Keane introduces Shaykh Bo’sen, the caravan guide, having reached Rabigh ahead of the caravan, sharing news of a Turkish cavalry patrol encountering theft, adding an air of tension to the otherwise restful night.

Turkish soldiers, initially perceived as protectors, become a source of annoyance to Keane due to his conspicuous fair complexion. Despite the challenges, the caravan finds some reprieve at Rabigh, allowing for a night of undisturbed rest under the moonlit desert sky. As the narrative unfolds, Keane’s vivid descriptions provide readers with a glimpse into the complexities of desert life and the camaraderie that develops amidst the hardships of the journey.

Respite and Recreation at Rabigh

Amidst the fortifications of Rabigh, the caravan finds moments of respite and recreation, providing a temporary escape from the arduous desert journey. Keane narrates the attempts of the pilgrims to indulge in a beach outing, only to be thwarted by the ever-deceptive mirage. The mirage, a constant companion in the unforgiving desert, once again plays its tricks, making the sea appear tantalisingly close yet elusive.

As the sun begins its descent, the atmosphere at Rabigh transforms into one of camaraderie and leisure. The evening brings an unexpected source of entertainment — pigeon shooting. Armed with guns, members of the caravan engage in this recreational pursuit, a brief departure from the challenges of the desert. The sound of gunfire reverberates in the air as the caravan, momentarily free from the constraints of the journey, finds solace in this shared activity.

Turkish soldiers stationed at Rabigh take on an unexpected role as protectors. Considered a deterrent against potential robbers, their presence offers a sense of security to the weary travellers. Despite the initial annoyance caused by the soldiers, the realisation dawns that, under their watchful eyes, the camp is shielded from the threat of theft or intrusion. The Turkish fort, once a distant and imposing structure, now becomes a reassuring guardian during the night’s rest.

The tranquillity of the camp, however, is not without its challenges. The haunting howls of dogs echo through the night, providing an eerie soundtrack to the desert landscape. Yet, amidst the discomfort caused by the persistent canine presence, the travellers find a certain comfort in the safety provided by the Turkish soldiers. The juxtaposition of these elements — the deceptive mirage, the recreational diversions, the watchful soldiers, and the haunting sounds of the desert night — paints a multifaceted picture of life at Rabigh, where moments of relaxation coexist with the ever-present challenges of the desert pilgrimage.

Culinary Misadventures: The Pigeon-Pie Denial and Pudding Fiasco

In the heart of Rabigh, the caravan experiences a culinary interlude that adds a touch of humour and discontent to their desert sojourn. Keane recounts the initial culinary ambition — an attempt to diversify the menu with a pigeon-pie. However, the aspirations of the pilgrims to savour this savoury dish are promptly thwarted as the Indian cook denies them this culinary delight. Whether due to limited resources or a protective inclination towards the designated “Englishistoo” provisions, the cook staunchly refuses to part with the essential ingredients for the pigeon-pie, leaving the pilgrims with unfulfilled gastronomic desires.

Undeterred by the denial, Keane, ever resourceful, proposes an alternative culinary venture — a rolly-poly pudding crafted from flour and treacle. The simplicity of the recipe and the feasibility of execution in the desert setting make it an appealing choice. However, the culinary journey takes an unexpected turn when the chief cook, perhaps feeling territorial about his culinary domain, decides to take charge of the pudding preparation.

What follows is a culinary mishap of epic proportions. The once-promising rolly-poly pudding takes on a bizarre and inedible form, defying the conventional expectations of shape and taste. The pudding, intended to be a comforting and simple treat, transforms into an eccentric culinary creation, prompting amusement and bewilderment among the caravan members.

Farewell to Rabigh: Departure Under Moonlit Skies

As the sun begins its descent, signalling the end of the caravan’s respite in Rabigh, preparations for departure unfold. The bustling energy of the caravan intensifies, and a palpable anticipation lingers in the air as the travellers ready themselves for the continuation of their desert odyssey. Against the backdrop of the setting sun, the caravan, once again, sets its course into the vast expanse of the Arabian desert.

The departure from Rabigh is marked by a chance encounter that adds a sense of interconnectedness to the desert landscape. The caravan crosses paths with another group of travellers, a caravan of Malays returning from Medinah. This serendipitous meeting introduces a brief but meaningful exchange, a convergence of journeys that momentarily binds the pilgrims in the shared experience of the arduous pilgrimage.

The departure, however, is not without its poetic undertones. The caravan chooses to venture into the night, guided by the brilliance of the moonlight that casts an ethereal glow over the desert terrain. The night sky becomes a celestial canvas, illuminating the path ahead for the travellers. Amidst the nocturnal journey, the moonlight unveils a haunting spectacle — the skeletal remains of camels scattered along the caravan route. The moonlight, both a guiding force and an illuminator of the desert’s stark realities, adds a layer of reflection to the caravan’s nocturnal progress.

Midnight Vigilance: Sentry Duty Amidst the Desert Silence

As the caravan ventures further into the desert, the narrative unfolds a chapter of silent vigilance — the midnight sentry duty assigned to the pilgrims. The stillness of the night becomes a canvas for the author’s reflections on the practicality and efficacy of these nighttime watches, highlighting the complex interplay between perceived security and the harsh realities of the desert.

The midnight sentry duty, a crucial aspect of desert travel, sees Keane reluctantly taking his post amidst the quietude of the desert night. However, his scepticism regarding the effectiveness of these vigilante measures is palpable. He questions the practicality of standing guard in a vast and largely featureless landscape, where the deceptive mirages and expansive silence seem to render the efforts of the sentries futile.

In the solitude of the night, the narrative takes an unexpected turn when an inadvertent incident disrupts the otherwise quiet watch. A sudden movement in the darkness, possibly mistaken for a threat, prompts Keane to take swift action. In an accidental discharge, a dog becomes an unintended casualty of the desert night, adding an element of surprise and tragedy to the narrative.