In the late 19th century, amidst the maritime tales of daring adventures, Jack Keane, a Yorkshire clergyman’s son, emerged as an intriguing figure whose contribution to early Arabaian travel writing remains relatively unknown to wider readership. Born on October 4, 1854, in the English port town of Whitby, Keane embarked on a remarkable journey that defied the norms of his time. His narrative unfolds against the backdrop of an era when European explorers seldom ventured into the sacred realms of Mecca and Medina. This essay delves into the detailed and authoritative account provided by Keane in his work “My Journey to Madinah,” shedding light on the challenges, landscapes, and interactions that characterised his time in Arabia.

False Starts and Camel Travel

Keane’s narrative plunges us into the heart of his journey, a journey marked by false starts and the unpredictable nature of camel travel. Laden camels, essential for traversing the arid landscapes, proved to be both companions and adversaries. The peculiar, jumpity-wabbledy gait of Mabarak, Keane’s camel chosen for the expedition, became a source of discomfort, jolting the riders into a state of despondency. The moonlit night, shrouded in darkness, set the stage for a challenging odyssey.

Night Travel and Mabarak

The moon, still in its youth, cast a feeble light on the travellers as they grappled with the hardships of night travel. Mabarak’s erratic movements not only disrupted the balance of the riders but also became a catalyst for a night of discomfort. The constant shift of weight and the jolting gait wriggled blankets off bodies, creating an atmosphere of perpetual unease. Keane’s vivid descriptions transport the reader into the very midst of the journey, where the struggle for comfort becomes a palpable experience.

Memories Triggered by Smells

As the journey continues, Keane’s senses are awakened, not just by the challenges of the night but also by the evocative power of smells. The odorous journey brings forth memories of Keane’s boyhood, reminiscent of a visit to a Hindoo burning-ground in Madras. The power of scents to recall long-forgotten memories becomes a recurring theme, subtly weaving personal reflections into the fabric of the desert odyssey.

Several writers have made observation to the effect that few things recall lost recollections like the “greeting of the nostrils by a long-forgotten odour.” I quite agree with them. Mabarak re- minded me perfectly of a scene of my boyhood. It was a visit to a Hindoo burning-ground in Madras…

John Keane: My Journey to Medina

Nightmarish Accompaniment

The moonlit night, intended to guide the travelers, transforms into a miserable experience compounded by the unsettling presence of a Bedouin camel-driver. The incessant shouts of “Sit forward,” “Sit back,” or “Sit in the middle” reverberate through the night, accompanied by the rhythmic clubbing of Mabarak’s hocks. Keane’s encounter with this desert guide, characterised by perpetual absence of mind, adds a layer of surrealism to the challenging journey.

Handling Confrontation

In an unexpected turn of events, Keane decides to take matters into his own hands, perhaps influenced by the wearisome journey. A subtle confrontation unfolds as he delivers a firm blow to the camel-driver, knocking him flat on his face in the sand. The act, initially surprising to Keane’s companion, is met with laughter from the author. This unconventional interaction sets the tone for Keane’s approach to challenges on the journey. Subsequent negotiations follow, revealing the Bedouin’s satisfaction at the prospect of resuming his ride. The encounter concludes with an agreement to pay for the mishap, highlighting the delicate balance of power and negotiation in the desert.

Setting Up Camp

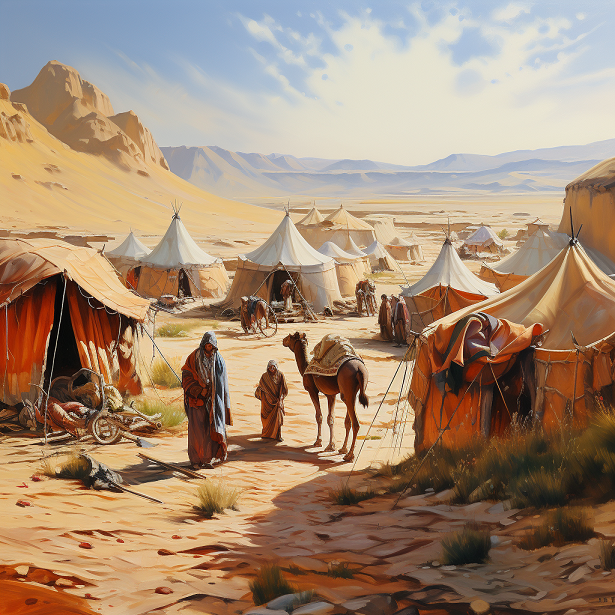

The arduous journey brings the caravan to a noonday halt in a level valley, where the ritual of setting up camp commences. The landscape, resembling others traversed on the journey, is characterized by sandy valleys, irregular rocky formations, and sporadic vegetation. The travellers, guided by Bedawin, establish a temporary settlement marked by rows of huts and designated spaces for each group.

As the camp takes shape, the communal efforts of the pilgrims manifest in the coordinated arrangement of tents, baggage, and camels. Keane’s observations shed light on the organised chaos that defines life in the camp – a juxtaposition of weariness and purpose. Multiple “laagers” form within the larger encampment, each group setting up its space, encapsulating a microcosm of the diverse travellers.

Our women were not allowed to dismount until their tent was ready for them, and then their camels were led close up to the entrance, and they made a little rush into the tent. After this our next duty was to pitch our own tent, and then to place the baggage, shugdufs, and shibriyahs round each tent, enclosing an open space of about fifteen yards in diameter,

John Keane: My Journey to Medina

The Bustle of Daily Life

Life in the camp unfolds with a distinct rhythm. Cooking activities commence, with open-air fires and the aroma of food wafting through the air. Bedouin girls and boys from the nearby village engage in commerce, offering goods such as milk, dates, firewood, and watermelons. Keane vividly captures the sights and sounds of the bustling camp, where weary travellers interact with local vendors against the backdrop of the desert.

Culinary Respite

The camp provides a temporary respite from the challenges of the journey. Cooks, equipped with simple utensils, prepare a meal of curry, rice, and chupattis. The communal dining experience, described by Keane, reflects the blend of culinary practices brought together by the diverse group of travellers. The distribution of rations to the Bedawi, accompanied by their habitual complaints, adds a touch of humour to the culinary interlude.

Essential Equipment

The success of the desert journey hinges on the careful preparation and utilisation of essential tools and provisions. Keane delineates the key components that accompany the travellers, ensuring their survival in the harsh desert terrain.

Bedding and Blankets

As the caravan navigates the shifting sands, the laden camels become mobile domiciles. Keane, amidst the discomfort of the journey, notes the challenge of maintaining balance on Mabarak, the designated camel. The blankets, essential for warmth during chilly nights, become both a source of solace and a potential source of loss as the camels continually shift their weight.

Water: Life’s Sustenance

Water, the elixir of life in the desert, is carried in traditional water skins. The nomadic Bedouin ensure a constant supply, and Keane’s narrative underscores the significance of this precious resource. The journey’s rhythm is punctuated by stops at wells, where the travellers replenish their water supply, providing a lifeline in the vast expanse of arid land.

Culinary Implements and Provisions

The camp’s culinary endeavours rely on basic cooking utensils and an open-air setting. Keane details the straightforward yet effective approach adopted by the cooks, who navigate the challenges of preparing meals in the desert. The provisioning of supplies such as curry, rice, chupattis, watermelons, dried fish, and dates showcases the diverse array of sustenance required for the journey.

Carrying Frames and Daggers

Shugdufs, the portable carrying frames, and Shibriyahs, a traditional dagger-like weapon, are indispensable companions on the desert trek. Keane provides insights into their usage, highlighting the practical considerations that govern their selection and utilization. These items, though seemingly mundane, play a crucial role in the daily routines and survival strategies of the pilgrims.

Tools of Defense

In the unpredictable desert environment, firearms assume a dual role – tools of defense and potential sources of conflict. Keane’s narrative reveals the handling of firearms within the caravan, emphasising the need for caution and expertise.

Diverse Pilgrim Groups

The caravan’s journey unfolds against a backdrop of diverse pilgrim groups, each contributing to the tapestry of the desert trek. Keane provides glimpses into the varied backgrounds, beliefs, and traditions that converge in this arduous pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina.

The Bedouin, nomadic dwellers of the desert, emerge as integral guides and guardians of the pilgrimage. Their expertise in navigating the challenging terrain and their role in orchestrating the camp setup showcase the symbiotic relationship between the Bedouin and the pilgrims. Keane’s observations underscore the nuanced interactions between the settled and nomadic communities.

Village Life Along the Route

The journey introduces encounters with villages along the route, offering insights into the daily lives of settled communities amidst the vast desert expanse. The exchanges with villagers, whether through commerce or shared spaces, provide a glimpse into the coexistence of disparate lifestyles amid the challenges of the desert environment.

Interactions with Locals: Challenges and Compromises

As the caravan progresses, interactions with locals, both Bedouin and settled communities, become pivotal moments. Keane narrates the challenges and compromises inherent in these encounters, shedding light on the delicate balance maintained to navigate cultural differences and ensure the pilgrimage’s smooth progression.