Gertrude Bell, a renowned explorer and author of “The Desert and the Sown,” embarked on extensive travels throughout the Middle East in the early 20th century, seeking to unravel the mysteries of the region’s diverse landscapes and cultures. Among her many journeys, the exploration of Jebel Druze in Southern Syria stands as a testament to her insatiable curiosity. Here, within the rugged mountains, Bell gained unparalleled insights into the lives of a secretive and obscure community, whose existence was intricately woven into the fabric of the Jebel Druze.

Key Takeaways:

- Gertrude Bell’s exploration of Jebel Druze unveiled the secrecy surrounding the community.

- Her encounters with figures like Milhem Ilian and Sheikh Muhammad en Nassar exposed the complex web of alliances and rivalries in the region.

- The Druze demonstrated resilience and saw a connection between their beliefs and global events, like the Japanese War.

- The journey highlighted the influence of exile on the perspectives of those like Muhammad en Nassar.

Sanctuaries of the Jebel Druze: Echoes of Ancient Faith

As Gertrude Bell ascended the tell in the Jebel Druze, she embarked on a journey that would unveil not only the rugged beauty of the landscape but also the ancient sanctuaries that graced its summits. Each tell in the Jebel Druze, it seemed, bore a sanctuary of its own, harkening back to a time long before the arrival of the Druze or the Turks in the region.

Bell pondered the intriguing history of these sanctuaries, speculating as to whether they were erected to honour Nabataean gods of rock and hill, reminiscent of Drusara and Allāt from the pantheon of Semitic inscriptions.

Were they erected to Nabataean gods of rock and hill, to Drusara and Allat and the pantheon of the Semitic inscriptions whom the desert worshipped with sacrifice at the Ka’abah and on many a solitary mound ? If this be so the old divinities still bear sway under changed names, still smell the blood of goats and sheep sprinkled on the black doorposts of their dwellings, still hear the prayers of pilgrims carrying green boughs and swathes of flowers As at the Well of El Khudr,

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

Inside each sanctuary, an enigmatic scene awaited the intrepid explorer. A structure resembling a sarcophagus, adorned with shreds of coloured rags, held the secrets of these ancient beliefs. Lifting the rags would reveal curious blocks of limestone, worn smooth by libations, reminiscent of the revered Black Stone at Mecca. Nearby, a stone basin for water could be found, even in the harshest weather conditions.

Bell vividly described the scene she encountered. On the day of her visit, the water in the stone basin was iced over, and snow had crept into the sanctuary through stone doors and roofs, forming muddy pools on the floor.

The sanctuaries atop the tells held an irresistible allure. They whispered of ancient beliefs, echoing rituals long past. They raised questions about the continuity of worship, as old divinities seemingly persisted under new names and forms. The juxtaposition of sacred spaces with the harsh realities of snow and ice highlighted the enduring spirituality of the land.

Discussion with An Ottoman Official

As Gertrude Bell continued her exploration of the Jebel Druze, the journey led her to a pivotal encounter with a key figure in the region, Milhem Ilian, a local Ottoman official. This encounter would shape their understanding of the challenges and complexities of the landscape and its inhabitants.

During their interaction, the conversation naturally gravitated towards their plans to explore the Safa, a volcanic wasteland to the east of the Jebel Druze. It was during this discussion that Milhem expressed concerns and reservations about the feasibility of their expedition.

Challenges in the Safa: The Ghiath Tribe

The insights of Milhem Ilian, a Syrian Ottoman official stationed amongst the local Druze community, shed light on the complex dynamics at play in the Jebel Druze. He revealed that the Ghiath tribe, inhabitants of the Safa, were in a state of unrest and defiance against the Ottoman Government. This tribal group had recently waylaid and robbed the desert post that connected Damascus and Baghdad, anticipating retribution from the Vali (Governor).

He thought the project impossible under existing conditions, for it seemed that the Ghiath, the tribe that inhabits the Safa, were up in arms against the Government. They had waylaid and robbed the desert post that goes between Damascus and Baghdad, and were expecting retribution at the hands of the Vali If therefore a small escort of zaptiehs were to be sent in with me they would assuredly be cut to pieces.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

Milhem’s assessment of the situation was grim. He believed that sending a small escort of zaptiehs (Ottoman gendarmes) with Bell and Mikhail would be futile and would likely result in their peril. However, he offered an alternative approach – suggesting that Bell might embark on the journey with the Druzes themselves, as they had a better chance of navigating the volatile situation.

The Promise of a Letter and a Potential Ally

Milhem Ilian also extended a lifeline to Bell in the form of a letter. This letter would be addressed to Muhammad en Nassar, the Sheikh of Saleh, described by Milhem as a trusted friend and a man of influence and judgement. The connection between these key figures hinted at the intricate web of alliances and rivalries within the Jebel Druze.

The Ghiath tribe’s relationship with the Druzes mirrored that of other tribes in the region, as their dependence on the high pastures during the summer made it imperative to maintain friendly ties with the Druze who dominated the Mountain. Milhem’s letter to Muhammad en Nassar held the potential to open doors for Bell’s planned expedition into the Safa.

Return Visit to Milhem’s House

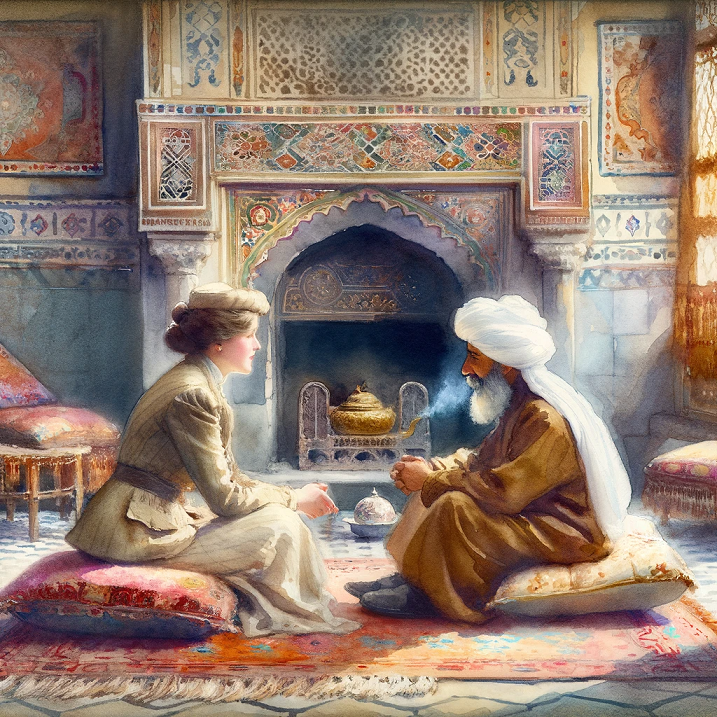

Bell’s curiosity led her back to Milhem’s house for a return visit. Milhem, a native of Damascus, opened his doors to her with a warmth that transcended the icy winds that swept through the Jebel Druze. As she entered, she found his room filled with people.

The gathering became an opportunity for Bell to share her recent experiences in the desert with her newfound friends. However, what she discovered during these discussions was a stark contrast to her perceptions. It became evident that the Druzes considered many of her friends as foes, and their only allies in this complex landscape were the Ghiath and the Jebeliyyeh tribes.

Tribal Rivalries and Alliances

In the Jebel Druze, allegiances were not straightforward. The Druzes navigated a web of rivalries and alliances that often transcended the physical terrain. The Sherarat, Da’ja, and Beni Hassan were among the tribes with whom the Druzes held blood feuds. This intricate network of relationships underscored the importance of maintaining alliances for survival in this challenging environment.

Bell’s observation of this complex social fabric deepened her understanding of the region’s dynamics. She likened the Druzes to those described by Kureyt ibn Uneif, a poet who sang of a people who, when confronted with adversity, would confront it head-on, either individually or in groups. This resilience and readiness for conflict were inherent traits of the Druze population, shaped by their history and surroundings.

Shared Observations on Religion and Society

The evening’s discussions took an interesting turn as the conversation shifted towards religion and society. Bell noted the difference between religious practices in towns compared to rural areas. The observation that religion seemed to wane in urban centres while thriving in the countryside prompted a lively exchange of ideas.

“You may find men in the Great Mosque at Damascus at the Friday prayers and a few perhaps at Jerusalem, but in Beyrout and in Smyrna the mosques are empty and the churches are empty. There is no religion any more.”

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

The group pondered the reasons behind this phenomenon. They debated whether the absence of want in urban areas led to a decreased reliance on religious faith. A Kurdish Agha present in the gathering, a man of wisdom and experience, shared his perspective. He attributed the decline in religious fervour in cities to the abundance of material wealth that rendered prayer and devotion less necessary.

The Farewell to Saleh

As Gertrude Bell’s journey through the Jebel Druze unfolded, each day brought new challenges and revelations. Her departure from Saleh marked the beginning of another leg of her expedition, and the treacherous terrain of the region posed both physical and logistical challenges.

Bell bid a fond farewell to the gracious hospitality of Sheikh Muhammad en Nassar and his family. The Sheikh’s house had offered her warmth, comfort, and insightful conversations during her stay. As she ventured out into the cold morning, the serene landscape of Saleh lay cloaked in snow and ice, a stark contrast to the inviting warmth of the Sheikh’s mak’ad (guest parlour).

Challenges of the Snow-Covered Terrain

The journey onwards was marked by the unforgiving cold of the Jebel Druze. The landscape, already rugged and challenging, was further complicated by a thick layer of snow. The deep snow covered the path and concealed hidden pitfalls, making it a formidable adversary for the travellers.

Bell and her companions had to navigate through the snow-covered hills, with mules and horses struggling to find sure footing. Deep drifts of snow presented a particularly perilous obstacle, causing the animals to stumble and their packs to scatter.

The region’s inhabitants, including the Druze, seemed to have deliberately designed a network of paths and trails that defied conventional notions of ease and convenience. These pathways were narrow, barely wide enough for two to walk abreast, and intentionally uneven to prevent rapid travel.

The intricate system of defence employed by the Druze showcased their resourcefulness in adapting to their environment. It ensured that outsiders would find navigating the terrain a formidable task, especially during the harsh winter months when the elements added an extra layer of complexity.

Passing Urman – A Village with Historical Significance

Gertrude Bell’s journey through the Jebel Druze continued, bringing her to the village of Urman. This village, with its unique historical significance and geographical challenges, added another layer of depth to her exploration of the region.

Urman was a village that had etched its name into the annals of history, not for its size or grandeur, but for its role as the epicentre of a significant event. It was in Urman that several years prior a revolt against the aristocratic El-Atrash landlords took place, leaving a lasting impact on the village and its inhabitants.

Milhem had entrusted my guide, Yusef, with the mail that had just come into Salkhad ; it consisted of one letter only, and that was for a Christian, an inhabitant of Orman, whom we met outside the village. It was from Massachusetts, from one of his three sons who had emigrated to America and were all doing well, praise be to God !

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

Arrival at Saleh

Gertrude Bell’s journey through the Jebel Druze had taken her to various villages and landscapes, each with its unique character and challenges. One significant stop along her route was the village of Saleh, where she experienced warm hospitality and engaged in insightful conversations with her host, Muhammad en Nassar.

All the Druzes are essentially gentlefolk ; but the house of the sheikhs of Saleh could not be outdone in good breeding, natural and acquired, by the noblest of the aristocratic races, Persian or Rajputs, or any others distinguished beyond their fellows.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

The evening at Muhammad en Nassar’s house was marked by engaging discussions on a range of topics. The global context of the time brought conversations about the Japanese War to the forefront. The Druze, like people worldwide, followed the progress of this significant conflict. Bell’s observations on the war sparked curiosity and discussion.

The Japanese War, unfolding far from the Jebel Druze, might seem distant in geographical terms. However, for the Druze people, it held a unique cultural significance. The Druze, like many communities worldwide, found common cause with the Japanese in this conflict.

The parallel drawn between the Druze and the Japanese was rooted in shared qualities. Both groups were perceived as displaying indomitable courage and resilience. The Japanese had demonstrated unwavering determination on the battlefield, traits that resonated with the Druze’s own reputation for bravery.

For the Druze, the Japanese War held a deeper meaning tied to their religious beliefs. Druze prophecy included the vision of an army of Druze bursting forth from the farthest reaches of Asia to conquer the world. This belief, while esoteric, had a profound impact on how the Druze perceived global events.

The topic that interested them most at Saleh was the Japanese War—indeed it was in that direction that conversation invariably turned, the reason being that the Druzes believe the Japanese to belong to their own race The line of argument which has led them to this astonishing conclusion is simple. The secret doctrines of their faith hold out hopes that some day an army of Druzes will burst out of the furthest limits of Asia and conquer the world.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

The Japanese War became, in the eyes of the Druze, a symbol of this prophecy. The Japanese, with their courage and success on the battlefield, were seen as fulfilling a destiny that aligned with the Druze vision. This connection served to strengthen the cultural ties that bound the Druze to the unfolding events in distant lands.

The Druze’s sympathy for the Japanese was further fueled by a sense of solidarity with the underdog. The Druze, who had faced their own challenges and adversities, found themselves rooting for the smaller, determined force in the conflict.

Foreign politics, particularly those involving England, also found their way into the discourse. Mr. Chamberlain’s name was known to the sheikh and his family, showcasing the interconnectedness of global events even in remote regions.

Muhammad en Nassar’s own experiences in exile added depth to the conversation. He had been among the sheikhs sent into exile following the Druze war, and his journey had taken him to Constantinople and Asia Minor. His firsthand experiences had provided him with a broader perspective on the world beyond the Jebel Druze.

the wholesale carrying off of the Druze sheikhs and their enforced sojourn for two or three years in distant cities of the Empire, has attained an end for which far-sighted statesmanship might have laboured in vain.

Men who would otherwise never have travelled fifty miles from their own village have been taught perforce some knowledge of the world ; they have returned to exercise a semi-independence almost as they did before, but their minds have received, however reluctantly, the impression of the wide extent of the Sultan’s dominions, the infinite number of his resources, and the comparative unimportance of Druze revolts in an empire which yet survives though it is familiar with every form of civil strife.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

During her exploration of Jebel Druze, Gertrude Bell delved into the veiled realms of a scarcely understood community, unwinding the complex tapestry of alliances, competitions, and lasting convictions that characterized the area. Her acute observations and interactions with local dignitaries are meticulously documented in Gertrude Bell’s literary works, providing invaluable insights into the enigmatic world of Jebel Druze.

Bell’s journey not only deepened our understanding of the Jebel Druze but also revealed the enduring spirit of its people, their unique perspectives on global events like the Japanese War, and the profound impact of their experiences on a larger geopolitical scale. Her exploration serves as a testament to the unyielding curiosity and resilience of both the Druze and the intrepid explorer herself, Gertrude Bell.

FAQ:

Q: What did Gertrude Bell’s exploration of Jebel Druze reveal?

A: It revealed the secrecy surrounding the Druze community and their unique dynamics.

Q: What insights did Bell gain from her encounters with Milhem Ilian and Sheikh Muhammad en Nassar?

A: She discovered the complex web of alliances and rivalries in the region, and their perspectives on global events.

Q: How did the Druze view their role in the Japanese War?

A: They saw themselves as fulfilling a prophecy, believing in a connection between their beliefs and the war.

Q: What impact did exile have on figures like Muhammad en Nassar?

A: Exile broadened their perspectives, providing them with a knowledge of the world beyond their village.

Q: What does Bell’s exploration highlight about the Druze and herself?

A: It underscores their resilience and unyielding curiosity, reflecting the enduring spirit of both.