In the early 20th century, Gertrude Bell, a renowned British writer and explorer, vividly captured the essence of her experiences in the tribal lands of Jordan. One particularly evocative account details her visit to a Bedouin sheikh’s tent, Fellah Al Issa, in the Balqa region, an encounter that elegantly illustrates the cultural and social norms of the time.

- Gertrude Bell’s journey reveals the enduring spirit and rich culture of the Arab people.

- The Age of Ignorance poetry provides deep insights into the Arab soul and its connection to the desert.

- Modern civilization poses significant challenges to traditional Bedouin nomadic lifestyles.

- Arabs express admiration for British governance in Egypt, highlighting a longing for stability and justice.

- The desert landscape serves as a backdrop for the complex interplay of history, culture, and change.

Bell’s narrative begins with a striking description of the setting. The sheikh’s tent, devoid of artificial illumination, relied solely on the flickering light of a fire. This created a dynamic interplay of light and shadow, casting the sheikh, Bell’s host, in an almost mystical light. At times, he was obscured by the pungent smoke from the fire, and at others, he was strikingly illuminated by the leaping flames.

The significance of Bell’s visit is underscored by the customs surrounding hospitality among the Bedouins. In honour of her arrival, a sheep was slaughtered – a traditional gesture of respect and welcome for a guest of consideration. This event paved the way for a bountiful meal, comprising mutton, curds, and flaps of bread, all consumed in the traditional manner using fingers.

When a person of consideration comes as guest, a sheep must be killed in honour of the occasion, and accordingly we eat with our fingers a bountiful meal of mutton and curds and flaps of bread.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

Bell’s observation here is not just of the meal itself but also of the eating habits of the Arabs. She notes that even on such festive occasions, the Arabs consumed surprisingly modest quantities of food, certainly less than what a European woman with a healthy appetite might eat.

Bedouin Daily Life & Diet

Bell notes the astonishing simplicity of the Bedouin diet. On ordinary days, when no guests are present, their meals typically consist of nothing more than bread and a bowl of camel’s milk.

But even on feast nights the Arab eats astonishingly little, much less than a European woman with a good appetite, and when there is no guest in camp, bread and a bowl of camel’s milk is all they need.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

The Bedouins’ ability to sustain themselves on such minimal fare is a testament to their resilience and adaptability to the harsh desert environment. Bell observes that the Bedouins spend most of their day engaged in leisurely activities, such as sleeping or gossiping under the sun. This laid-back lifestyle, however, does not diminish their remarkable endurance. She recounts seeing the ’Agel, a group of Bedouins, undertake a four-month march, subsisting on this same modest diet.

This aspect of Bedouin life highlights not only their physical endurance but also a certain philosophical acceptance of their environment. Despite their minimalistic lifestyle, Bell notes a certain leanness and thinness among the Bedouins, a physical manifestation of their constant brush with hunger. She points out that any sickness in the tribe can have severe consequences due to their generally frail health. This observation offers a poignant insight into the fragility of life in the desert and the Bedouins’ uncomplaining acceptance of their circumstances.

Local Tensions

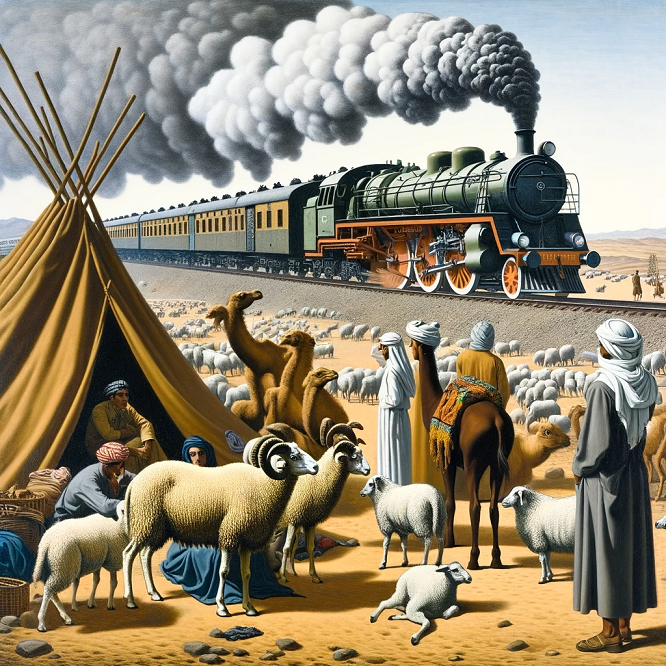

Bell describes an engaging dialogue between Fellah ul Tsa and her travel guide, Namrud, which throws much light on the predicament faced by the Bedouin tribes due to the encroachment of civilisation. This encroachment manifests in various forms, most notably the gradual occupation of their summer quarters by fellahin (peasants) and, more distressingly, the takeover of vital summer watering places by Circassian colonists. The Circassians, described by Bell as “industrious and enterprising”, were settled in eastern Syria by the Ottoman Sultan following their displacement from the Caucasus by the Russians.

The Circassians are a disagreeable people, morose and quarrelsome, but industrious and enterprising beyond measure,and in their daily contests with the Arabs they invariably come off victors. Recently they have made the drawing of water from the Zerka, on which the Bedouin are dependent during the summer, a casus belli, and it is becoming more and more impossible to go down to ’Amman, the Circassian headquarters, for the few necessities of Arab life, such as coffee and sugar and tobacco.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

Bell’s account provides a clear indication of the changing dynamics and the pressure exerted on the traditional Bedouin way of life. The discussion highlights the dilemma faced by the Bedouin tribes: whether to seek government intervention to protect their interests or to avoid such involvement due to the fear of military service imposition, cattle registration, and other undesirable practices.

The Influence of External Governance

Continuing her insightful exploration of Bedouin life, Gertrude Bell recounts a conversation that pivots to the subject of governance, particularly the impact of foreign rule on indigenous communities.

Namrud, a participant in the discussion, expresses admiration for the English rule in Egypt, a sentiment not universally shared but significant in the context of the period. He describes, with a sense of awe, the effectiveness of the English legal system, particularly in dealing with theft. He narrates an incident where a zaptieh (policeman) successfully recovers stolen camels through a process that is both just and straightforward. This anecdote serves to highlight the stark contrast between the local methods of conflict resolution and the more structured approach under English administration.

all over Syria and even in the desert, whenever a man is ground down by injustice or mastered by his own incompetence, he wishes that he were under the rule that has given wealth to Egypt, and our occupation of that country, which did so much at first to alienate from us the sympathies of Mohammedans, has proved the finest advertisement of English methods of government.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

Interestingly, Fellah ul ’Isa, listens with interest but remains non-committal about the prospect of adopting such foreign rule. This hesitation reflects a deep-seated wariness of external control, a sentiment rooted in the desire to preserve traditional ways of life and autonomy.

Bell provides a personal anecdote from her past, where Druze sheikhs in the Hauran mountains inquired about seeking refuge under Lord Cromer in Egypt, should the need arise. This inquiry, and Bell’s diplomatically evasive response, underscores the complex relationship between local communities and foreign powers.

The Druze sheikhs of Kanawat had assembled in my tent under shadow of night, and after much cautious beating about the bush and many assurances from me that no one was listening, they had asked whether if the Turks again broke their treaties with the Mountain, the Druzes might take refuge with Lord Cromer in Egypt, and whether I would not charge myself with a message to him. I replied with the air of one Weighing the proposition in all its aspects that the Druzes were people of the hill country, and that Egypt was a plain, and would therefore scarcely suit them.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

Through these conversations and reflections, Bell paints a picture of a region at a crossroads, grappling with the allure of stability and order offered by foreign governance and the deep-rooted desire to maintain independence and traditional ways of life.

Historical and Cultural Insights Through Poetry

Gertrude Bell’s narrative gracefully transitions into an exploration of the rich cultural heritage of the Bedouins, as reflected in their poetry. Bell recounts an interaction sparked by her curiosity about ancient Arab customs and language. She enquires about certain phrases and expressions, leading to a discussion about their origin and continued relevance. This inquiry ignites interest among the Bedouins, who are astonished to learn that these phrases predate the Prophet Muhammad and are still in use. This revelation serves as a testament to the enduring nature of their linguistic and cultural traditions.

The conversation then shifts to the poetry of famed Arab poets such as ’Antara and Lebid. Bell highlights the significance of their work, which eloquently encapsulates the essence of the Arab spirit and wisdom. These poets, through their verses, touch upon various facets of life, love, heroism, and the inevitable passage of time.

All poetry is ascribed to ’Antara by the unlettered Arab ; he knows no other name in literature.

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

Reflections on Bedouin Resilience and Modern Challenges

Bell’s musings are particularly poignant as she considers the future of the Bedouins in the face of modernisation and external influences. She notes that the lands traditionally inhabited by the Bedouins are increasingly becoming suitable for urban settlements, a shift that poses a significant challenge to their nomadic lifestyle. This change forces the Bedouins to confront a critical decision: either adapt by building villages and cultivating the land or retreat further into the harsher regions of the desert, where life is even more challenging.

The truth is that the days of the Belka Arabs are numbered. To judge by the ruins, it will be possible, as it was possible in past centuries, to establish a fixed population all over their territory, and they will have to choose between themselves building villages and cultivating the ground or retreating to the east where water is almost unobtainable in the summer, and the heat far greater than they care to face

Gertrude Bell: The desert and the Sown 1907

This dilemma encapsulates the broader theme of Bell’s narrative – the tension between the preservation of traditional ways of life and the inevitable push towards modernisation. She observes that while the Bedouins have historically thrived in their environment, their future is uncertain in a world that increasingly values settled, agricultural, and industrialised ways of life over nomadic traditions.

Through her narratives, Gertrude Bell offers a compelling portrait of a community at a crossroads, caught between the allure of progress and the desire to maintain a deeply rooted cultural identity. Her reflections provide valuable insights into the struggles and resilience of the Bedouins, serving as a testament to the enduring spirit of a people adapting to an ever-changing world.

FAQs:

Q: What does Gertrude Bell’s journey in the desert reveal?

A: It reveals the enduring spirit and rich culture of the Arab people.

Q: What significance does the poetry from the Age of Ignorance hold in Bell’s observations?

A: The poetry provides insights into the Arab soul and its deep connection to the desert.

Q: How does modern civilization impact the traditional Bedouin lifestyle?

A: Modern civilization, exemplified by the encroachment of Circassian settlers, poses significant challenges to the Bedouins’ nomadic way of life.

Q: What are the Arabs’ views on British governance in Egypt?

A: Arabs express admiration for British governance, highlighting a longing for stability and justice.

Q: What role does the desert landscape play in Bell’s narrative?

A: The desert landscape serves as a backdrop for exploring the interplay of history, culture, and change in the Arab world.