In the early 20th century, Harry St. John Philby embarked on a series of explorations across the Arabian Peninsula, documenting his findings in the seminal work, “Heart Of Arabia.” Through his extensive travels in Arabia, Philby provided a detailed account of the customs, economic practices, and daily life in regions such as Hasa, Wadi Dawasir and Riyadh. His interactions with local tribes, insights into the trading dynamics at various ports, and observations on the socio-economic structures offer a unique glimpse into the fabric of Arabian society during this period.

- Customs tariffs in Arabia are directly inspired by the Quran, emphasizing a spiritual basis for economic policies.

- Despite its prohibition, tobacco enjoys a paradoxical tolerance, highlighting the complexities within legal and social norms.

- The Arabian economy features a blend of currencies, including the Riyal, Indian rupees, and special tokens like the Tawila.

- The importance of camels in trade and transportation underscores their pivotal role in the Arabian socio-economic landscape.

- Regional port competition, especially with Bahrain and Kuwait, significantly influences trade dynamics and economic strategies.

Customs and Tariffs in Ibn Sa’ud’s Arabia

Philby’s exploration of Al Uqayr begins with an examination of the customs tariffs in Ibn Saud’s nascent kingdom, which Philby refers to as ‘Wahhabiland’, a region adhering to a taxation system directly inspired by Islamic teachings. The imposition of an 8% added value rate on all imported and exported goods is a practice enshrined by the Prophet Muhammad, signifying a timeless adherence to the Quran’s directives. This universal rate underscores the integration of religious principles into the economic fabric of Wahhabiland, offering a unique perspective on how spiritual guidance shapes fiscal policy.

Special Case of Tobacco

A notable exception to the general customs policy is the treatment of tobacco, which is subject to a 20% duty. Despite the Quranic injunctions leading to a prohibition of its import (as explained to Philby by his hosts), Philby uncovers a paradoxical tolerance towards tobacco, revealing the complexities within the region’s legal and social norms. This divergence is further highlighted by the clandestine consumption of tobacco, including by officials such as the Director of Customs and his brother, in private settings. Philby’s narrative, “though its import into the territories of Ibn Sa’ud is prohibited under the direst penalties,” illustrates the nuanced balance between official edicts and social practices.

Currency and Financial Instruments

In the ‘heart of Arabia,’ the economy operates on a fascinating blend of traditional and foreign currencies. The Riyal, and the Maria Theresa dollar, emerge as the standard currency, a symbol of the region’s historical trade connections. Alongside, Indian rupees circulate freely, showcasing the economic ties between Arabia and the Indian subcontinent. Philby’s account highlights the fluidity of currency usage, reflecting the adaptability of the Arabian market to global economic currents.

Small Change and Special Tokens

The intricacies of the Arabian financial system extend to the realm of small change and unique monetary tokens. The Masqat haiza, equivalent to the Indian paisa, serves as the everyday currency, facilitating local transactions. In a singular innovation, the Hasa region employs a special copper token, known as Tawila, underscoring the localised solutions to currency needs. These tokens, along with the limited acceptance of Indian and Turkish coins, illustrate the diverse and pragmatic approach to currency within the Arabian Peninsula.

Gold and International Trade

Philby’s observations reveal a notable preference for tangible assets in international trade, with gold being readily accepted. This preference for gold over paper money, which is virtually unused in the interior, speaks to the traditional values and the skepticism towards modern financial instruments. The absence of paper currency in internal transactions and the reliance on gold and other physical currencies underscore a deep-seated reticence towards abstract financial systems, highlighting a broader mistrust of modern banking practices within the fabric of Arabian society.

Trade Dynamics and Port Activities

The economic vitality of Arabia, as witnessed by Philby, is significantly bolstered by the customs revenue collected at the Hasa ports. In 1917, a year marked by war and restricted shipping, the customs duties funnelled approximately Rs.4 lacs into the coffers of Riyadh. This figure, though reflective of a tumultuous period, suggests a substantial potential for revenue under normal circumstances, hinting at the strategic importance of these ports in the Arabian economy.

Import Sources and Trade Routes

The merchants of Hasa, according to Philby, predominantly source their goods from the Indian markets, indicating a strong commercial bond between Arabia and the Indian subcontinent. This trade route not only facilitates the flow of goods into the Arabian interior but also represents a critical artery of economic sustenance for the region. The reliance on Indian imports highlights the global interconnectedness of local economies and the pivotal role of maritime trade routes in sustaining regional markets.

The Value and Role of Camels in Trade

In a striking depiction of the local economy, Philby notes the central role of camels, not just as beasts of burden but as pivotal assets in the Arabian trade network. The escalated value of camels, particularly noted during the war years, underscores their significance in the transportation and trade systems of the region. The rise in camel prices, from a mere 20 dollars to a range of 80 to 150 dollars, illustrates the economic prosperity and the increased demand for these animals, highlighting their indispensable role in the Arabian socio-economic landscape.

Regional Port Competition and Economic Strategies

Bahrain and Kuwait’s Influence on Trade

Philby meticulously outlines the strategic economic rivalry between the Hasa ports and their neighbours, Bahrain and Kuwait. This rivalry significantly impacts the flow of goods, with Bahrain levying duties on consignments intended for Najd during transshipment, thereby diverting the bulk of Central Arabian trade towards Kuwait. Here, goods pay duty only once to Shaikh Salim Al-Sabah, illustrating a nuanced manipulation of trade flows and customs duties to economic advantage. This dynamic not only underscores the competitive nature of regional ports but also the broader geopolitical strategies that influence trade in Arabia.

Ibn Sa’ud’s Economic Challenges

The narrative further delves into the economic quandaries faced by Ibn Sa’ud, who, despite being a significant figure, seems to be at a disadvantage due to the prevailing trade practices. Philby suggests that the economic principles and the potential benefits of leveraging geographic and strategic advantages have not fully penetrated the courts of Arabian princes, including Ibn Sa’ud. This lack of economic strategising is portrayed as a missed opportunity for optimising trade benefits and enhancing revenue streams for Ibn Sa’ud’s territories.

Potential for Port Development

Philby speculates on the future of Arabian trade through the lens of port development, particularly focusing on ‘Uqair and Jubail. The development of these ports is presented as a long-term solution to the economic challenges faced by Ibn Sa’ud, potentially altering the regional trade dynamics. However, such development is also acknowledged as a costly and time-consuming endeavour, requiring significant investment and strategic planning. This section of Philby’s account highlights the intersection of economic ambition and practical challenges in the quest to improve Arabia’s standing in the regional trade network.

Encounters with Local Trade and Transportation

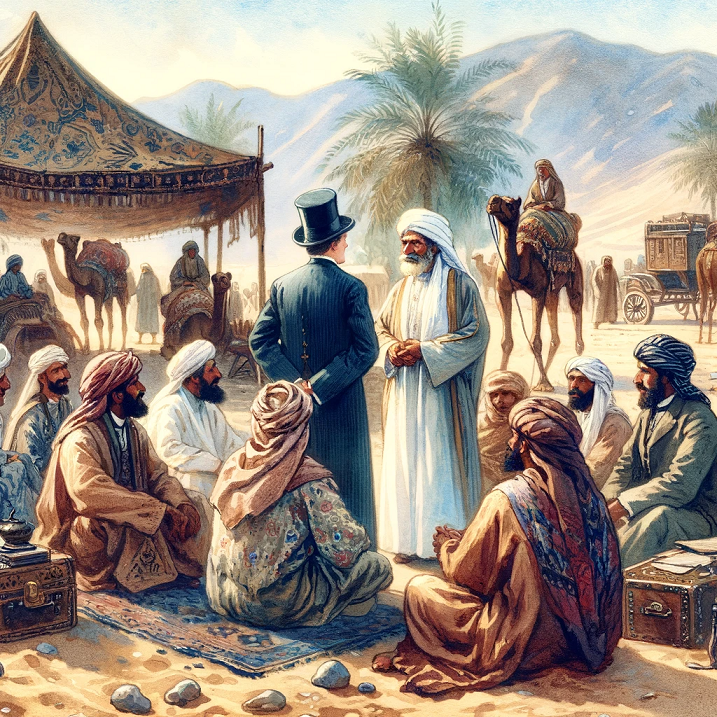

Philby’s narrative vividly brings to life the bustling activity and vibrant trade practices at Arabian ports. His description of groups of camels appearing over the sand-hills, the animated exchanges between boat-crews and cameleers, and the peculiar sight of great white asses of the Hasa, offers a colourful tableau of daily life. These encounters, set against the backdrop of uncouth Badawin marvelling at Philby’s foreign attire, provide a rich tapestry of cultural and economic interactions. The dynamic flow of goods and people, as described by Philby, encapsulates the essence of Arabian trade and transport, highlighting the enduring spirit of commerce that defines the region.

Logistical and Administrative Challenges

The complexities of navigating Arabian trade logistics are laid bare through Philby’s experiences. His anticipation for an early start on a journey, only to be met with delays and the absence of arranged transportation, underscores the unpredictable nature of logistical planning in the region. The suggestion by the Amir to opt for donkeys instead of camels, as a solution to the unfulfilled promise of camel arrivals, further illustrates the everyday challenges and the need for flexibility in plans and expectations.

Harry St. John Philby’s “Heart Of Arabia” serves as a compelling chronicle of early 20th century Saudi Arabian society, providing insightful observations into the customs, economic strategies, and daily life within the region. Through his detailed account, Philby offers a window into the complex interplay between traditional practices and the economic imperatives of trade and commerce.

FAQ

Q: What is the basis for customs tariff in Wahhabiland?

A: The customs tariff is inspired by the Quran, fixed at 8% ad valorem.

Q: How is tobacco treated differently in terms of customs duty?

A: Tobacco is taxed at 20% despite its official prohibition.

Q: What currencies are used in the Arabian economy?

A: The Riyal, Indian rupees, and special tokens like the Tawila are used.

Q: Why is gold preferred over paper money?

A: Gold is preferred due to traditional values and mistrust of modern banking.

Q: What role do camels play in the Arabian economy?

A: Camels are crucial for trade and transportation, reflecting their high economic value.

Q: How do Bahrain and Kuwait affect Arabian trade?

A: They influence trade dynamics through strategic port competition and customs duties.

Q: What kind of challenges did Philby face during his travels?

A: Philby encountered logistical and administrative challenges, highlighting the need for adaptability.