In the early 20th century, Harry St. John Philby embarked on an extraordinary journey to Saudi Arabia, an adventure chronicled in his seminal work, “Heart of Arabia.” Through his vivid descriptions and insightful observations, Philby offers readers a unique window into the life, culture, and landscapes of a region at a crossroads of change. His narrative not only encompasses the bustling markets and serene oases but also delves into the intricate social fabric of the Saudi people, including townsfolk, the nomadic Bedouin, and the influence of Turkish governance. Philby’s exploration of places like the Qaisariyya, the Rifa’ quarter, and the springs that breathe life into the desert unveils the complex tapestry of Saudi Arabia, providing a rich context for understanding the dynamics of its cities, such as Hufuf and the surrounding areas.

- The Qaisariyya serves as the cultural and economic heart of Hasa, showcasing a blend of local craftsmanship and Indian wares.

- Governance in Hasa is characterized by its simplicity, with a focus on imperial needs rather than modern administrative systems.

- Water resources are central to Hasa’s agriculture, with springs and streams enabling the cultivation in an arid landscape.

- The military aspect of Hasa combines traditional warfare strategies with modern armaments, showcasing a transition period in military preparedness.

Qaisariyya: A Cultural and Economic Hub

Al-Qaisariyya, positioned to the east of the main Suq in Hufuf, emerges in Philby’s account as a labyrinth of arcades, where the air is filled with the chatter of merchants and the vibrant display of goods lays a feast for the eyes. This marketplace, with its roofed and open sections, serves as the beating heart of commerce, housing an array of permanent shops. From grocers to cloth-merchants and carpet-sellers to metal-workers, the Qaisariyya is depicted as a microcosm of the bustling economic life in Saudi Arabia. Philby’s portrayal brings to life the eclectic mix of merchandise, predominantly sourced from India, alongside the local craftsmanship in metals, wood, or leather, marking the area as a confluence of indigenous and foreign influences.

The Qaisariyya is not just a commercial center but also a social hub, where “townsmen and Badawin” converge in search of bargains, driven by a restless desire to spend as long as they have money to do so. This vivid depiction underscores the vibrant economic activity and the cultural melting pot that characterizes the marketplace. Among the notable wares, black mantles adorned with simple silver or gold-thread filigree work stand out, underscoring the region of Hasa’s reputation for exquisite craftsmanship. Philby notes, “with this one exception, however, there seemed to be little in the place of any real merit, and prices ranged high,” highlighting the unique value placed on these garments amidst a wide array of goods. This statement not only reflects the economic considerations of the time but also hints at the discerning tastes of the local populace, further enriching the cultural narrative of the Qaisariyya as a pivotal economic hub in the heart of Arabia.

The Rifa’ Quarter

Within the fabric of the town lies the Rifa’ quarter, a district that Philby describes as the residential heart for merchants and individuals of wealth. This quarter, enveloping the Qaisariyya and sprawling across the eastern side of the town, represents a stark contrast between the public vibrancy of the marketplace and the private opulence of the merchant class. The external modesty of these dwellings, constructed from the ubiquitous limestone and coated in a mixture of juss or mud, belies the speculated luxury within. Philby lamentably notes his missed opportunity to witness this luxury firsthand, “Unfortunately owing to the shortness of our stay I had no opportunity of seeing the interior of any house but the Sarai,” suggesting a hidden world of comfort and affluence that remains elusive to the transient visitor.

The Suq al Khamis and Na’athil Quarter

The Suq al Khamis, coming alive on Thursdays, transforms into a bustling hub where the community’s rhythm is marked by the ebb and flow of traders and customers. This weekly market becomes a focal point for the exchange of goods ranging from dates to meats, with Philby observing the traditional bargaining that animates these transactions. He describes the scene with a touch of admiration for the local customs, where “no sheep or goat is bought but is first kneaded by expert hands.”

Contrastingly, the Na’athil or slum quarter presents a different aspect of the town’s social fabric. Here, the streets narrow and the houses, stripped of plaster, wear an air of neglect. Philby remarks on the less elegant and sometimes ruinous condition of these homes, offering a glimpse into the stark disparities that characterise urban living spaces. A narrow street, serving as a demarcation line, segregates this quarter from the Rifa’, symbolising the physical and metaphorical divisions within the community.

Through Philby’s eyes, the residential and commercial quarters of the town unfold as a mosaic of contrasts, from the concealed luxuries of the Rifa’ to the vibrant commerce of the Suq al Khamis and the palpable neglect of the Na’athil. These descriptions not only map out the geographical divisions but also sketch the social hierarchies and economic disparities that define the town’s character.

The Salihiyya Suburb and Its Historical Context

The narrative takes a turn towards the Salihiyya suburb, a relatively recent expansion lying outside the southeastern fortifications of the town. Named after a Turkish-built fort intended for the city’s protection, Salihiyya’s inception is rooted in the era of Ottoman influence, serving as a residential area primarily for Turkish officers and their families. This was a necessity, as Philby notes, due to the lack of “sufficient or suitable accommodation” in the more congested parts of the town, notably the Kut.

Philby’s account reveals a fascinating transition within Salihiyya, from its origins as a bastion of Turkish administrative and military presence to its assimilation into the local fabric following the Ottoman withdrawal. He introduces figures like Muhammad Effendi and Khalil, who, despite their origins in the old regime, have become “deep-rooted in the soil of their adoption,” serving the new masters with the same zeal as before. This transition is emblematic of the broader shifts occurring in Saudi Arabia during Philby’s exploration, where the remnants of Ottoman rule gradually blend into the emerging national narrative.

Moreover, Philby’s reflections on Salihiyya touch upon the broader themes of cultural integration and the resilience of communities in adapting to political changes. The suburb, with its historical ties to the Ottoman era and its evolution into a part of the town’s landscape, serves as a microcosm for studying the impacts of colonial legacies and the processes of post-colonial adaptation. Through Philby’s eyes, Salihiyya emerges as a testament to the complexities of cultural and political transitions in early 20th century Saudi Arabia.

Governance, Administration, and Finance in Hasa

Philby offers a glimpse into the administrative simplicity that characterises the governance of Hasa, painting a picture of a society where the necessities of modern administration such as education, sanitation, and public lighting are conspicuously absent. This absence, however, is not portrayed as a deficiency but rather as a deliberate choice, aligning with the region’s priorities and values. Philby succinctly captures this ethos, stating, “Simple is the administration of an Arab town — no education, no sanitation, no illumination, and therefore no expense and no taxation except on what we should call ‘imperial’ account.”

Central to the narrative of Hasa’s governance is the figure of Muhammad Effendi, a person of significant influence in the local financial administration. Philby describes Effendi’s pivotal role in tax collection and the management of Hasa’s finances with a blend of admiration and skepticism. Effendi, a veteran of the Turkish administration, opts to stay on after the Ottoman retreat, navigating the complexities of the local financial system with a dexterity that ensures the smooth flow of revenues to Riyadh. His tenure exemplifies the continuity of expertise amidst political change, yet Philby hints at the opacity of Effendi’s methods, suggesting a financial acumen that borders on the enigmatic: “No questions are asked so long as a plausible balance-sheet and a substantial balance are remitted at irregular intervals to Riyadh.”

The financial backbone of Hasa, as Philby outlines, rests on customs dues and Zakat or land-tax, with the latter being particularly noteworthy for its contribution to the regional treasury. This tax system, while seemingly rudimentary, is lauded for its effectiveness in encouraging agricultural productivity and self-sufficiency among the local populace. Philby’s observation that “such a system, far as it falls short of the principles of scientific assessment, has at least the merit of giving tenants every encouragement to improve their holdings” underscores a broader theme of governance in Hasa: a balance between tradition and the pragmatic needs of the community.

Agriculture and Water Resources

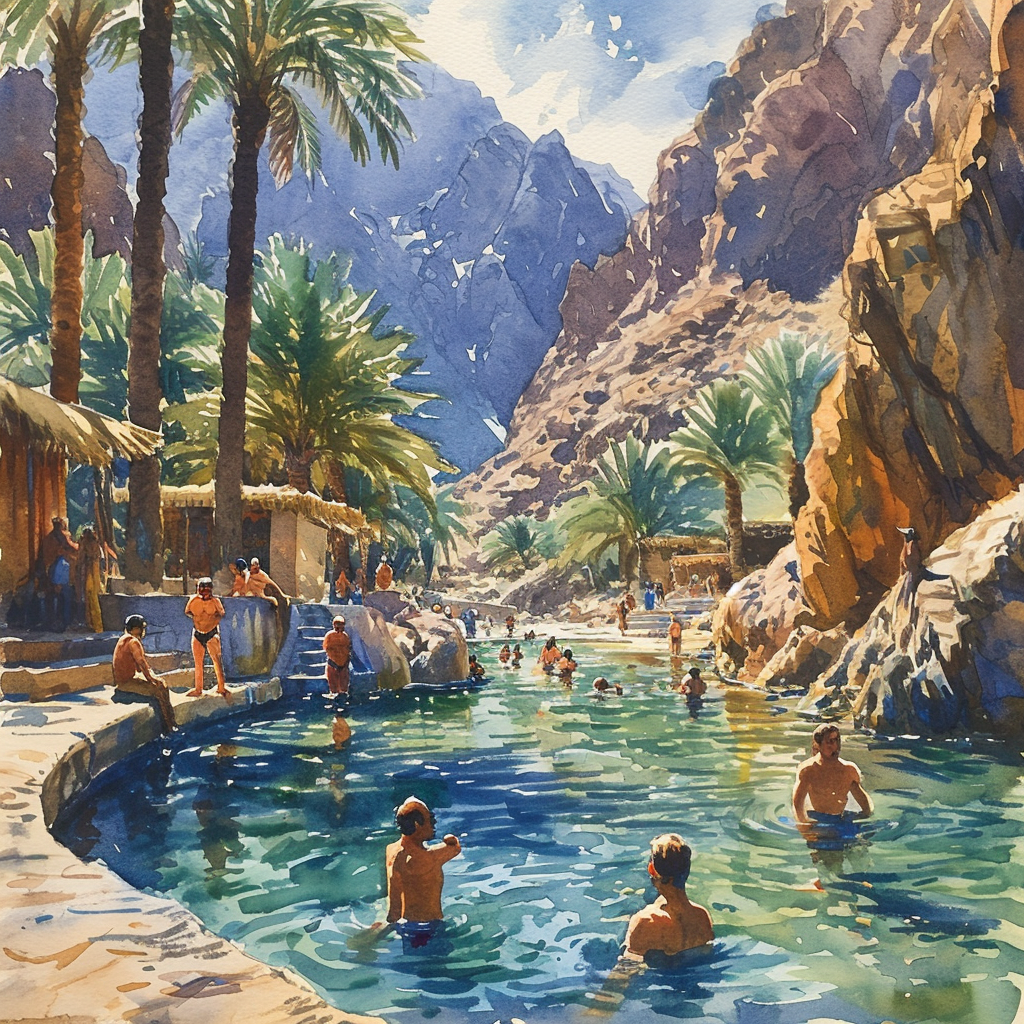

In the arid landscapes of Saudi Arabia, the sustenance and prosperity of communities like those in Hasa hinge on the availability and management of water resources. Philby dedicates a significant portion of his narrative to the springs and streams that are the lifeblood of agriculture in the region. He eloquently describes the “wealth of the Hasa” as lying in its mineral springs, running streams, and abundant water, painting a vivid picture of an oasis of fertility in the desert’s heart.

Central to the agricultural success of Hasa are the major springs, including the renowned ‘Ain al Harra, which Philby describes as “bubbling up distinctly hot into a large tepid lake.” This and other springs, through a network of open channels, facilitate a system of irrigation that supports the cultivation of dates, wheat, rice, and a variety of fruits and vegetables. The strategic use of water, as depicted by Philby, showcases a harmonious balance between human ingenuity and the natural environment, enabling the region to flourish despite its harsh climatic conditions.

However, Philby does not shy away from highlighting the challenges posed by “wasteful methods of irrigation” and the absence of a regulated system of water management. He notes the detrimental effects of excessive water use on the land, pointing to areas where the soil has been tried sorely, manifesting in patches of marsh and groves of decadent palms. This critique underscores a critical aspect of sustainability and environmental stewardship that was beginning to emerge in Philby’s time.

Military Aspects and Strategic Importance

The military dimension of Hasa, as observed by Philby, reveals a fascinating interplay between traditional warfare strategies and the introduction of modern armaments. Within the fortified walls of the Kut, or citadel of Hufuf, lies a repository of Hasa’s military strength, juxtaposed with its historical and architectural grandeur. The citadel, with its “thick-walled fortress” and the majestic mosque of Ibrahim Pasha, symbolises the confluence of cultural heritage and strategic military considerations.

Philby’s account sheds light on the peculiar status of the citadel’s armament, comprising both antiquated cannons of “antediluvian type” and modern weaponry, including machine guns presented by the British government. This eclectic arsenal, though impressive in diversity, is critiqued for its practical utility; Philby notes the ironic underuse of these modern arms, with “three of the former [machine guns] were still in the packing-cases in which they had arrived.” The narrative conveys a sense of missed potential in military preparedness, further emphasised by the mention of the local garrison’s unfamiliarity with the sophisticated machinery, a point underscored by Philby’s observation: “but the real trouble and disappointment lay in the fact that of the four men who had been specially instructed in the management of machine-guns…three were already dead, and the survivor, Husain by name, had apparently forgotten most of what he had learned.”

Despite these limitations, the strategic importance of Hasa’s military capabilities is not understated. Philby contemplates the broader implications of armed strength in the region’s power dynamics, reflecting on his initial belief that “Ibn Sa’ud’s Arabs might be able to make good use of guns if available.” Yet, his subsequent experiences and observations of the skirmishes in the region lead him to a nuanced conclusion about the effectiveness of traditional Arab warfare strategies over reliance on modern artillery.

In “Heart of Arabia,” Harry St. John Philby provides an intricate mosaic of Saudi Arabia’s Hasa region, blending vivid descriptions of its marketplace dynamics, residential quarters, and the lush oasis that fuels its agriculture with insightful commentary on its governance, military readiness, and the complexities of water resource management. Through his journey, Philby unveils the essence of Hasa, a land where tradition and modernity intersect against the backdrop of a stark yet nurturing landscape.

Q: What is the Qaisariyya known for?

A: It’s known for being a cultural and economic hub with a mix of local and Indian goods.

Q: What characterizes the Rifa’ quarter?

A: It’s characterized by merchant residences that hint at luxury behind modest exteriors.

Q: What role does the Suq al Khamis play in local culture?

A: It serves as a vital weekly market, underscoring the community’s social and economic life.

Q: How does the Salihiyya suburb reflect Hasa’s history?

A: It shows the lasting Turkish influence and the community’s adaptability to change.

Q: What defines governance in Hasa?

A: Governance is marked by simplicity and a focus on traditional rather than modern needs.

Q: Why are water resources crucial in Hasa?

A: They enable agriculture in the desert, making them vital for survival and prosperity.

Q: How does Hasa’s military aspect reflect its culture?

A: It illustrates a blend of traditional strategies and modern technology, highlighting a period of transition.